The Early Penguin Travel and Adventure Titles – The "Cerise Series"

This article is closely based on two articles that appeared in The Penguin Collector in December 2007 and December 2008. It is designed to accompany Duncan Smith’s www.penguincerisetravel.com. The site is images supported by text, this is text supported by images. Feel free to travel between them.

Introduction

Penguin Books started in August 1935. They had striking typographical covers and were colour coded by subject matter. Fiction was the characteristic ‘Penguin Orange’. The firm was just 13 months old when the first ‘Travel and Adventure’ title, The Dark Invader, was published in September 1936. It was Penguin No. 60 and had a cerise – that is cherry pink – cover. In the next 23 years about 90 such titles appeared. Outside they all look very similar, the ‘horizontal grids’ up to 1953 and the remainder with ‘vertical grids’, often, as shown here, with added illustration.

The rest of this article is about the insides – hence more biographical and geographical than graphical. In other words, the where, when and who of what the books are about. But to start with the why. One assumes Allen Lane, founder of Penguin, chose available titles that had sold fairly well in hardback and tried them out on the new sixpenny market – nice colour, middlebrow entertainment. The world when they were published was a little different, there were still some unexplored bits (three books are about pioneering new air routes), and we still had an Empire. ‘We should give credit to the gallant gentlemen who gave their lives to win one more country for the flag’, writes Mr Monckton in his introduction to one early title. So many books are not easy to summarise in a few words, but I shall do as travel writers themselves do, concentrate on just the interesting bits.

The Who and the What

There are about sixty authors in all, no-one has more than three titles. Four are what one might call established literary figures: Graham Greene, D.H. Lawrence, Vita Sackville-West and Aldous Huxley. A few others are established travel writers: Norman Douglas, J.R. Ackerley, Freya Stark, Karen Blixen, Peter Fleming and, as the last title, Gerald Durrell. Other than that, one is dipping into the well of the largely forgotten, from which depths I briefly rescue one smart lady and one intrepid young man – see below. None of the titles are particularly rare. The only title to mention the print run is Sledge (193), ‘Mr Lane tells me that he is printing 50,000 copies’.

Travel writing has a long, ongoing and fairly respectable history (see the recent Penguin Great Journeys series) for, though there is less world left to explore, there are still many travellers, both real and armchair. But Adventure – this word today has something of an old-fashioned or adolescent sound to it (five titles include the word, while two omit it from the cover). Martin Lindsay, author of two early titles, can open a chapter, ‘Polar exploration is not a science, rather it is something between an art and a sport – it is the quest for adventure that sends men to the polar regions’. However, its geographical successor, Venture to the Arctic, (Pelican 432, 1958) is, by contrast, much more serious, in effect a collection of scientific papers. Like all Penguin genres, there are fuzzy boundaries. The first volume on the World War II Russian Campaigns was cerise (467), but the second was grey (518, World Affairs). Flying Dutchman (139) is a cerise autobiography.

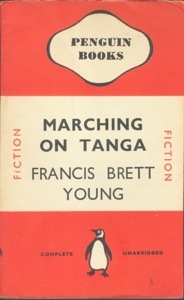

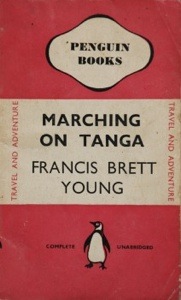

But there were two outright mistakes, Marching on Tanga – with General Smuts in East Africa by Francis Brett Young (261, 1940) appeared, at first edition, in an orange fiction cover. It was soon corrected by a reprint. This also happened to Evelyn Waugh’s When the Going Was Good (825) – extracts from four of his earlier travel books were labelled as fiction in 1951. It was not to be corrected for some years. Other lesser blunders are that the Essential T.E. Lawrence (1155) has 1015 on the spine and ‘Graham Green’ appears on the spine of The Lawless Roads (559). He was not amused.

On the other side of the frontier, Denton Welch’s Maiden Voyage (979) which began in ‘biography blue’ in 1954, was later reissued in the Penguin Travel Library (9522). Cedric Belfrage’s Away From It All, also blue, is really a travel book. The dark blue biographies of Captain Scott (207) and Nansen (661) are other marginal cases as are the letters of another intrepid lady traveller, Gertrude Bell. These came out as early Pelicans.

The Where and the When

Settings are very varied: brave polar explorers, Mediterranean and south sea island pleasure seekers and intrepid ladies (eight of them) getting along with the natives in lands far away. One book, Sporting Adventure (424), is about wildfowling (bird watching with a shotgun!) and never leaves the UK. But the main division is between peace and war. Up to 1945, a quarter of the books have wartime settings, three set in the Second World War, two by Spanish Civil War participants (Tom Wintringham and Arthur Koestler) and the remainder, including the first, in the Great War, as it was called when Penguin started. The last include the five so-called ‘caged Penguins’ about PoW escape attempts as well as two by air aces (149 & 360) the former being one of the two termed ‘a Flying Penguin’.

Almost all the books describe events in the twentieth century and hence within the lifetimes of most readers. Those that go back further, having staying power, are a tad more interesting. There are two nineteenth century American classics, Two Years before the Mast (578) and The Oregon Trail (678). Both were to be reissued with introductions in the American Library series in the 1980s. Then there are two historical anthologies, again one wet, one dry: Sea Escape and Adventures (426) and African Discovery – An Anthology of Exploration (619). Two others take us back further: edited extracts from Lord Anson’s voyage in the 1740s (607) and Siamese White (294), a piece of original historical research into an English East India Company adventurer in the 1680s.

There are eight titles set in the Arctic – four of them with overlapping personnel – but only two set in the Antarctic where most penguins come from. The only cerise title with a Penguin Companion entry is Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s The Worst Journey in the World. This because it is part of the Penguin story, chosen to mark the first round number – Penguin 100 – in 1937. It began as two volumes, 99 & 100 and was then reprinted as one 570 page double volume, 100, in 1948. ‘I am glad it is coming out in Penguins: after all it is largely about penguins’, the author added in his new preface. This is a bit of an exaggeration, but it is a very readable account of Scott’s last expedition. After Cherry-Garrard’s death in 1959, it was republished with redrawn maps and a new foreword replacing the author’s interesting, but now outdated, introduction. This appeared as a 650 page Penguin in 1970, not cerise but still with the 100 number. South Latitude by F.D. Ommanney (417), though chiefly about being beastly to seals and whales, mentions penguins too. At one point they attract the attention of the rescue party by hoisting a flag stained red with penguin blood. Disgraceful.

In Search of Gino and Rosita

Gino Watkins and Rosita Forbes – who? But Rosita was the only lady to contribute three titles and Gino the only explorer to lead three expeditions (see 148, 233 & 133). Let’s start with Rosita. Her three travels over land were to or through Libya (113, 1937), Abyssinia (205, 1939) and Russian Road to India by Kabul and Samarkand (290, 1940). Lord Allenby, who wrote the foreword to 205, calls her a friend and her book ‘a travel tale of rare brilliance and convincing truth’, while others quoted praising her include Compton Mackenzie and Anthony Eden.

Her career, says one blurb, ‘reads like something out of a wonder book’. As I was, I think, nine, when I read my last wonder book this was not particularly helpful. But it does go on to tell us that she ‘drove a flying ambulance’ during WW1 and later twice met Hitler. Her approach is serious and the books give little away – one has four appendices and a glossary. One index has over forty entries for herself (Rosita.. encounters a severe gibli; Rosita.. bargains for festal sheep; etc.). A gibli is a sandstorm. We also discover she wrote five novels; sadly, none is in Penguin. The picture, right, reveals an amazing hat, much fur and, if you look carefully, a wedding ring. Ah, but which husband? A quick google (500+ hits) reveals she started life as a Miss Torr and went on to marry two colonels, Forbes being the first. She died Mrs Arthur McGrath, FRGS in Bermuda in 1967. Though two of her books are in print on Amazon, one travel book site says she has not worn well. I have to agree. Freya and Vita are more fun and write better.

The Penguin archives at Bristol University include Rosita’s letters to Allen Lane about delays in the publication of Russian Road. There are six of them, all hand written and full of a cheerful indignation about delays in publication. One she sent without a stamp to attract Allen Lane’s attention!

Gino (Harold George) Watkins led an expedition across Labrador in 1927-28 at the tender age of 22 (recounted by Jamie Scott in The Land That God Gave Cain, No. 148). He then led another across Greenland (see 233). While preparing for another Greenland trek he was drowned. Watkins’s Last Expedition by F. Spencer Chapman (133, 1938) is named in his emory. L.P. Kirwan’s A History of Polar Exploration (Penguin 1705, 1962) calls him ‘adventurous and volatile’ and also reveals that Jamie Scott went on to write his biography. Mr Chapman’s book also uses a word familiar to some us – anorak. It being new to his readers he explains its (original) meaning. All early Penguins were reprints of earlier hardbacks and, while firsts of such as Cherry-Garrard change hands for large sums, others can be found quite cheaply. The Land That God Gave Cain hardback came out in 1933 and cost 12/6d (62.5p), 25 times the cost of the Penguin. My second hand hardback cost £10, only about three times what you might expect to pay for a clean first of the Penguin. I must confess that moving to the hardback with its wide margins, photographs and better quality paper was a bit like moving from steerage into first class.

Later Times

There were 12 vertical grid cerise titles with numbers over a thousand and they include works by Aldous Huxley and T.E. Lawrence and cover designs by David Gentleman and Paxton Chadwick. The last were three titles by Gerald Durrell, popular and often reprinted in other formats. I have seen a 65th reprint of My Family and Other Animals, which may be a record. The distinctive pictorial ‘Abram Games’ covers titles include two with cerise spines (1238 & 1250, both 1957). Then they went orange, and then orange and black. Among the latter are the popular Kon Tiki Expedition and The Crossing of Antarctica. But these later titles are for another time.

Recycling its backlist being an important part of Penguin business, how has the cerise community fared since? On the whole, not very well. Only four made it into one or more of the Modern Classics series: Edmund Blunden’s Undertones of War (82) which includes 32 of his poems, J.R. Ackerley’s Hindoo Holiday (242), Karen Blixen’s Out of Africa (913) and Graham Greene’s The Lawless Roads (559).

In the 1980s the B format Penguin Travel Library appeared. There were about 90 titles and a dozen one-time cerise titles (not including Rosita) were included as reissues. Norman Douglas’s Together (502) exists as a rare ‘Services Edition’ and, more recently, has made it onto a coffee mug.

Recycling its past once again, in September 2007 Penguin published 36 ‘Celebration’ titles, contemporary writers but with traditional horizontal grids, colour coding and spine numbers. Three of them (4, 14 & 18) are cerise – though it is a pity they are referred to on the back cover as pink. But they are the real colour and the real thing.

Conclusion

Researching this article was an adventure in itself, a venture into a slice of under-explored Penguin territory. Now you’ve read the book, go see the picture. Visit Duncan Smith’s www.penguincerisetravel.com for more details on some of the authors and a fine collection of images. My checklist of titles is also available for serious students of the genre, and myself and Duncan are keen to contact any other enthusiasts for these bygone slices of history, geography and popular publishing.